Hello! Welcome to our book club post for June 2025. This month we read Lolita by the wonderful Vladimir Nabokov. We hope you enjoyed this as much as we did – I can’t remember the last time I was as genuinely blown away by a book than this.

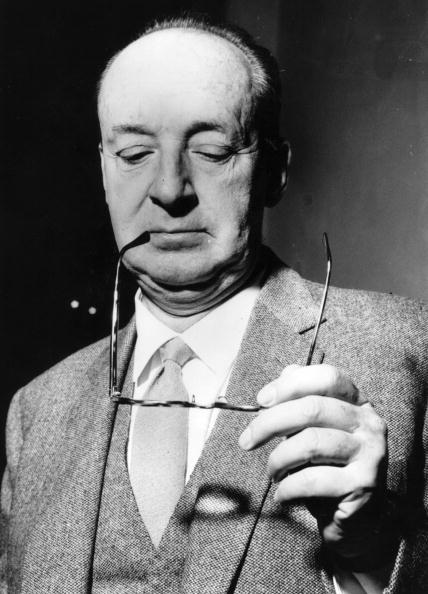

We would recommend you watch this video – we found it really insightful to hear the way that Nabokov speaks. Interviews with him seem to be rare and few between, and so this is well worth the watch. Anyway, enjoy our thoughts – you will find our communities comments at the bottom along with a form where you can send in your own opinions! Please do, we love to hear! See you next month for… Another Country by James Baldwin. : )

June’s Book Club. Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov

The thing is, with literature and art and I guess all creative endeavours, the word ‘masterpiece’ is so easily thrown around. And it’s a big word. It refers to a triumph – to something outstanding. For a piece of art to be a true masterpiece, there can’t be hundreds of others as well. And so, when I hear people refer to this book or that book as a ‘masterpiece’ I am often weary and critical going into reading it. Does is deserve that title? If it doesn’t, why do people so easily give it?

But then I read Lolita. Suddenly, all other books that have been heralded as masterpieces by critics and reddit users and friends and family all fizzled out. There was no question about it, Nabokov’s Lolita stood tall. It is, for me at least, the true masterpiece of modern literature.

There has been no book before that has left me so speechless and so deeply impressed than this. Nabokov’s crafting of language and narrative, his characters and relations and world and toils and tears and everything that lives within these pages – wow.

I finally finished reading this book about 48 hours ago now, and despite having many things to fill up my day with and occupy my thoughts, my mind keeps finding a way to return to it. It returns to the rich images that Humbert describes and poor, poor Lolita whose cards were dealt so damn unfortunately.

Humbert Humbert and His Moral Complexity

I think perhaps what I am mainly compelled to think about is Nabokov’s mastery of storytelling, how he created a character – Humbert – so vividly that despite his actions, there was part of me that found it hard to dislike him. Sure, I despised the things he did to our poor Lolita, but Nabokov makes it so that he does as well. Humbert feels no pride in his perversion, in fact, he writes incredibly intelligently and logically about how wrong it is. And still, as the novel progresses and his delusion heightens, we follow with his narration and in a sense, start to become deluded with him. This is not to say that I found his actions to Lolita justifiable, no. It’s only that as they travel around the country, Humbert notes his sexual encounters with Lo (and thoughts surrounding) less and less that I almost stopped thinking too critically upon them. And then every so often pops up a scene which brings you to back the reality of their night-times encounters and you are reminded that our narrator is tilted Humbert Humbert and Lo is 12.

What is so grand about this book is that nobody but Nabokov would have had the guts to write a novel which revolves around the topic of pedophilia in the way that he does. He brings forth questions that people are afraid to even discuss, perhaps for fear of being accused or just pure, genuine hatred and impenetrable beliefs. It is known to humanity that sexual attraction towards children is wrong and unjustifiable, nobody is denying that – but what Nabokov questions is a topic of interest.

Was Humbert plagued by his attraction to children? Were his thoughts beyond his control? Is he doomed by them, and does he deserve sympathy? If so, to what degree, and at what point does this sympathy end. Before he acts upon his thoughts, when they are merely that – thoughts deep within the crevices of his mind – is he evil then?

Nabokov was able to raise these questions very well though the character of Humbert Humbert – a well-educated, good looking and respectable man with complete self-awareness. And then, his desires overwhelm his thoughts, and it is then perhaps where he becomes evil and entirely unforgiveable.

Addiction, Delusion and Descent

Upon reading, it seemed that there were some parallels between Humberts attraction (and actions there-upon) and the notion of addiction. It is as if we, as readers, were introduced this completely rational and reasonable man in Part 1, and then as the novel progresses his ability to cling onto the person he is declines within his indulgence of his desires. Somewhere along their travels deep within the “oatmill hills” of North America or the hazy hours spend in those “sunset motels”, he loses himself. His once restrained thoughts become his continuous actions as his established rationality become his delusions. It is only when Lolita escapes him, and he tracks her down to ask for her return that this delusion breaks, and the real Humbert returns.

“I’ll die if you touch me,” I said. “You are sure you are not coming with me? Is there no hope of your coming? Tell me only this.”

“No,” she said. “No, honey, no.”

She had never called me honey before.

“No,” she said, “it is quite out of the question. I would sooner go back to Cue. I mean—“

She groped for words. I supplied them mentally (“He broke my heart. You merely broke my life”).”

The Ending: A Quiet Tragedy

What perhaps struck me the most was Humbert’s final description of the outdoors on the final pages and the subsequent epiphany he has in that moment. Humbert final acknowledges that he had broken Lolita’s soul, and he doesn’t do this by hearing her scream or cry or yell, but by the simple acceptance of the absence of her laughter in the crowd. Nabokov doesn’t make it overly dramatic or too ‘in your face’. Instead, he crafts this beautiful yet rather simple picture of the world around him and then notes Lolita’s absence from it. And is it his fault that she is not there living a normal life. And then that is his turning point where he really understands the severity of the harm that his actions have caused, the irreversibility of it all and the pain that poor, poor Lolita will forever feel.

Why Lolita Still Haunts Readers

The ending of this novel is unfathomably incredible. Truly, genuinely fine, fine literature.

His direct acknowledgment of how the “blood still throbs in my [Humbert’s] writing hand”, manages to describe as much detail necessary, and in that moment, Humbert is real. Humbert is a real man crouched over a real desk, maybe lit by the dim glow of a flickering candle or the stark harshness of a secluded rooms’ artificial light. Nevertheless, he is there, crouched over a desk scribbling away the voice inside his head as his pen bleed his thoughts and he is just as real as the words you are reading.

The way with these words that Humbert possesses – he could have been so much more. In another life perhaps he is a great poet. Perhaps instead he scribbles grand describes of the endless mountains that he and Lolita never drove across, and generations long after he is dead and buried can read over them, again and again. And maybe Lolita does preserver with her tennis and is able to make it into the world of professional sportsmanship. Or maybe she lives out her life quietly, alongside her mother in her home in Ramsdale besides the lake. And maybe she cares for her mother as she ages, until she peacefully dies in her sleep how she should have. And then they never do cross paths and both Humbert and Lolita are able to keep themselves. Without Humbert’s interference, at least she would have had that.

But not in this life. And so now Lo lives eternally in these pages, without a voice or a future or a mother or a life. And forever she is just the nymphet of Humbert Humbert, sleeping in ever-changing motel rooms and crying and crying and crying and crying as her innocence is stolen a little more day by day. The eternal existence of the girl with the silky skin and scarlet lips has been crafted by poor old Humbert Humbert, the man who broke her soul.

The Ploughman’s Community Comments

Melissa, US: After watching the movie and hearing so many public opinions on this (including book covers and ‘Lolita fashion’) I was shocked when I finally read the book. Lolita is a child! An innocent child who knows no better. She is not seducing him. The way this book has been received in history is disgusting! What a piece of literature, and what a shame it is so misunderstood.

Charles, Ireland: I agree – this was a really interesting take, how Nabokov manipulates our empathy. I kept seeming to forget that Lo was 12. What a writer!

Eva, Denmark: What a masterpiece this is. A true masterpiece – I agree with you on that for sure.

Aggravating-Bill-387, Reddit User: Wow. I was so impressed by your thoughts on Lolita! This part stood out to me SO MUCH.

“But not in this life. And so now Lo lives eternally in these pages […] crafted by poor old Humbert Humbert, the man who broke her soul.”

I genuinely cried reading this. You are so correct.

There is truly no “Dolores Haze”. Her legacy, her memory is nothing more than the sexualized, soulless shell that he viewed her as, that he created her as. In the fictional book, she died a poor young woman without any family besides her husband. In reality though, Humbert, or rather the genius of Nabokov, created a pop culture icon, a “Lolita”, a new definition in the dictionary, a clothing style and aesthetic that is popular all these years later. Book covers of seemingly smug and promiscuous young girls exemplify this inversion of intended perception. Society created this phenomenon, this concept of “Lolita”. Ignorantly blinded by the enticing and compelling attraction, society has overlooked the true purpose of this novel for decades, which is, horribly simplified, a cautionary tale of sexual perversion. Society’s reaction and perception of Lolita is the exact reflection of what Nabokov sought to call out for unjustness.

Our Response: I am glad you have mentioned the pop-culture concept of ‘Lolita’. It is something that rather disgusts me, and it was very important when looking for a photo of the front cover for it not be one with a sexualised young girl on the front! As you say, for Nabokov’s intention to be to call out unjustness, and then for society to perceive his character of Lolita in this perverse way says a lot. Thank you for reading our post and your kind words.

Leave a comment