Welcome to our book club for October 2025… We hope you enjoyed reading one of Dostoevsky’s finest works. The great Crime and Punishment not only tells a captivatingly devastating narrative, but also delves into the philosophies of those living in St Petersburg, Russia in the late 19th Century. It is a true literary sensation. To put some images of St Petersburg at the time in your mind, we would recommend to you to have a watch of this video before reading our post. Enjoy!

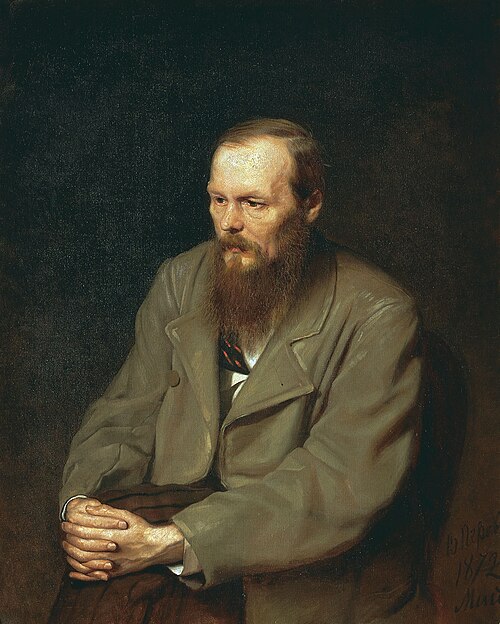

October’s Book Club. Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky

Crime and Punishment has had a lasting impact on the way I seem to perceive life – that being my philosophies and subsequent actions. I think perhaps the most prevalent of this impact comes from within the first 50 pages or so, before our Raskolnikov propels himself into his guilt-fuelled paranoia and isolation. Before our story really begins with the murder of our pawnbroker, when the novel is perhaps less narrative-driven, this is where Dostoevsky’s ideas are perhaps most clear.

The idea which remains closely in my thoughts, long since I have returned Dostoevsky to my bookshelf, is introduced within Raskolnikov’s encounter with Marmeladov in the dusty, underground tavern. There Marmeladov sits, alone and weary looking, slowly sipping on his beer. Who Raskolnikov describes to us is that of a deeply saddening character: a man with deep intelligence in his eyes, yet nestled far beneath a distant, empty stare and a scraggy- looking appearance. Upon verbal introduction to Marmeladov, we discover his reason for drinking alone at this dirty bar. He seeks sorrow. In telling Raskolnikov of the cold and harsh conditions himself and his poverty-sticken young family live in, he says:

“That’s why I drink, for it is in drink that I’m trying to find sympathy and compassion. It is not happiness but sorrow that I seek. I drink, sir, that I may suffer, that I may suffer more and more!” p32

It’s this concept that I find interesting, shocking even, yet damningly relatable. Drink, alcohol, drugs, all of these substances are often thought to bring about some kind of short-term joy. Some escapism of your current troubles and a thrust into finite peace and contentment. But what if that is what you do not seek?

This drink for Marmeladov, often vodka but sometimes beer, is not a pathway to ecstasy, it’s a companion for his torment. It’s a way to sit, and perhaps if you will, enjoy the pain, not escape it. To confront this feeling, this upset and turmoil that follows you and say: “I can face you now, sit with me as I sit with you though all my days.”

There is something beautiful within the companionship between sorrow and one’s undivided attention. In a cold St Petersburg bar, Dostoevsky portrays this wonderfully.

The scene concludes with Raskolnikov returning his new friend, Marmeladov, home. As the pages continue, it is revealed that this father of three has been on a five day bender, in which he has spent the entirety of his family’s income. In the economic setting of Crime and Punishment, urban-poverty is widespread, and this income that has been frittered away in Marmeladov’s self-indulgence could mean the difference between a small portion of food and elongated hunger.

Upon entrance to the house, Marmeladov’s wife jumps up on him, shrieking as she attacks her husband. Raskolnikov looks around the squalid place and sees the young children hungry. Special attention is paid towards Sonia, the eldest, who has begun to sell herself to bring in money for the family. Her income, at 18 years old, goes to making her body more desirable with makeup and aiding her father’s drinking habits.

Unannounced and unnoticed, our student-boy Raskolnikov departs the scene, silently placing a handful of copper coins on the family’s windowsill. In need of money himself, he instantly regrets this decision but upon realization of his inability to revoke the charity, he rationalizes it in his mind as:

“Sonia must have her makeup.” p 44

Some things, at whatever cost to us, just have to happen. I’m not quite sure why this concept has stayed with me through the years. I suppose it is just rather comforting. Perhaps if I find myself to be more charitable that I can afford, or devote more time that I have to a cause unbeneficial to myself, I will rationalize my self-inflicted detriment by telling myself that Sonia must have her makeup. That is a truth.

Last winter, I was walking past a small Tesco store with a friend, on my way to watch my flatmates’ panto performance of ‘A Little Mermaid’. As we passed the store, a man who seemed to be homeless asked if we could buy him some food. It was a cold evening with icy winds not too long after payday, and so I obliged. And when I asked what this man would like, he looked at me to explain that if I walked right to the end of the store, there was a refrigerated aisle which held a selection of trifles. He explained that the one he wanted was the Tesco’s Finest Triple Belgium Chocolate Trifle. A bit confused, expecting to pick up a sandwich or something similar, I found myself at the self-service checkout with a £4.50 chocolate trifle outlined as a desert for four. I grabbed a wooden fork and then gave it to the man, who thanked us casually. We walked away with me scratching my head in confusion and my friend giggling at what had just happened. I’ll be honest, I did feel a little forlorn that I had just spent over half of my daily budget – I was a student at the time – on a chocolate trifle for some random man, but in my head popped in Rascolnikov’s rational phrase:

“Sonia must have her makeup.”

The man must have his trifle. Some things just have to be. And that’s just the way it is.

The Ploughman’s Community Comments

Ari, USA: I have a difficult relationship with Crime and Punishment. I am glad to have read it… however, I don’t know if I entirely understand the need for the length of the novel. But I am sure it was for a reason, then again this book was published over 150 years ago, so I guess our reading habits (and attention habits) may have changed since then!

VoidSurfer0x7A, Reddit User: Facing his family, getting sober, trying again, that would be heard, humiliating work. Sorrow, on the other hand, is: familiar, strangely comforting and easier than responsibility. “Sonia must have her makeup” is such a haunting line though.

Conor, Australia: The final image of this book, WOW. I will never forget Raskolnikov crying in Sonia’s arms. His realisation that he is just human. One of the best books I have ever read, thank you.

Lois, Netherlands: This concept you have explained of drinking for sorrow completely went over my head when I read those pages. It is a rather interesting take, I never have thought of drinking in that way.

Anonymous Reader, Netherlands: Happened to stumble across this website. I’ve read Crime and Punishment in Dutch about a year and a half ago. The manner of drinking which you describe I can relate to very well. I’d even admit to saying this is the only way I drink, when going out as well, except for dinner time.

Leave a comment